[ad_1]

In case you are wondering why we have an adorable picture of a happy baby as our feature image, its not a cheap trick (well, maybe it is, but there’s a reason!) In Buddhist belief, we are taught that we are born without memories of previous lives — and although it may lack scientific logic, it makes perfect psychological sense. Even though we cherish our memories, we grow through our future actions. Imagine the crushing weight of being born with full memories of our past lives. It would be devastating and debilitating.

In Buddhism, Rebirth is a different concept than Reincarnation — since Buddhism does not have a belief in the eternal soul — but rather, the concept of Buddha Nature [Subtle differences alert! For a feature on Buddha Nature, see>>]. This does lead to some angst among devoted Buddhists who wonder why we are reborn, life after life, compelled by the forces of karma.

Rebirth is often symbolized with the metaphor of a butterfly. The Blue Morpho — one of the world’s most beautiful butterflies — with its iridescent blue color — is also one of the largest, with up to an eight-inch massive wingspan. Butterflies are one of the most common symbols of reincarnation around the world. It is the symbol used for the logo of our new “sister” publication True Rebirth [TrueRebirth.com] [Sneak Peak of TrueRebirth.com at the link, it’s not fully launched yet!]>>

A Reader Asks About “What” is Actually Reborn

In this week’s “A Reader Asks” we try to answer reader K. D’s question. [Full question inset below.] K.D. questions the logic of the laws of karma — the repercussions of negative and positive actions on our future lifetimes — especially when Buddhism teaches there is no “self” or ego to be reborn. (This may come down to labels and language — or not — since Buddha never actually denied “self” — see Sutta references below.)

It’s a very profound, well stated and difficult question to answer, but we’ll do our best…

This is an advanced topic that is discussed in numerous sutras (suttas), but it is always a difficult concept. As always, in Buddhism, it comes down to discussions on language, labels, and perceptions.

The biggest misunderstanding here, is in the doctrine of No-Self — which does not mean any existence. We’ve cited the two most prominent Sutra references on this below. But, there’s a lot of nuance to this sophisticated question that goes beyond “no-self” doctrine.

Rebirth philosophy in Buddhism informs us that we have been born previously and will continue to be born until we are finally liberated by realizations leading to Enlightenment. Why, then, do we not remember our past lives? Even though we don’t remember our past actions in past lives, why do they influence our present and future lives? These are difficult questions to answer. In Buddhism, all life is a continuum, without beginning or end. There are subtle differences between the concepts of reincarnation — which posits an eternal soul — and rebirth which doesn’t even discuss soul. Why is it not discussed? Because Buddha identified our ego and attachments as the cause of our suffering. Taking refuge in a concept of an eternal soul — instead of the Dharma teachings — will ensure Samsara continues. Removing the “me” and the “ego does not mean “no existence.”

Ultimate (no language) and Relative (labeled)

To help understand it, teachers often answer on two levels: ultimate and relative. Buddha often used Similes — notably in this case the water snake similes and the raft simile (both below.) At the “relative level” what is reborn is similar to a soul, although that “Buddha Nature” is “boundless” and inseparable from all. At an ultimate level, there is no distinct “me” to be reborn; but at the relative level — where most of us “exist” there is “self.”

Before we begin, we should apologize to K.D. — there won’t be direct, simple answer. And, a lot is opinion. However, the key to the question lies in the definition of “I” or “we” which is never an easy one — and for that, we can only quote the Buddha (see below, Sutta references.)

Rebirth is a journey.

The bottom line, though, is that by clinging to “me” or “I” we remain attached to the suffering of Samsara. However, by negating the “I” and “other” we were embracing “boundlessness” or “fullness” rather than “singleness” that is subjected to clinging — but that’s not the same as saying we don’t exist. We certainly exist — it’s just a lot less lonely (joking). As always, in Buddhism, this comes down to perceptions.

“I have no self” and “I have self”

As teacher Thanissaro Bhikkhu wrote in a commentary to the Alagaddupama Sutta [English translation below]:

“Thus the view “I have no self” is just as much a doctrine of self as the view “I have a self.” Because the act of clinging involves what the Buddha calls “I-making” — the creation of a sense of self — if one were to cling to the view that there is no self, one would be creating a very subtle sense of self around that view (see AN 4.24). But, as he says, the Dhamma is taught for “the elimination of all view-positions, determinations, biases, inclinations, & obsessions; for the stilling of all fabrications; for the relinquishing of all acquisitions; the ending of craving; dispassion; cessation; Unbinding.”

Thus it is important to focus on how the Dhamma is taught: Even in his most thoroughgoing teachings about not-self, the Buddha never recommends replacing the assumption that there is a self with the assumption that there is no self. Instead, he only goes so far as to point out the drawbacks of various ways of conceiving the self and then recommends dropping them.

The self is separated from the true nature of the reality only by virtue of ego. The ego clings to notions such as “I” which lead to concepts of “I need” and “I want.” These lead to samsara. “I want” leads to greed which leads to stealing, war, and other negative karmas. These karmas cling to us from one “I” life to the next.

Reader’s Full Question: Very Specific Concern

K. D.’s Reader Question: “I have a very specific question I’d like to ask that has been bothering me for a while and is beginning to cause me doubt. No one can seem to answer it to satisfaction. Maybe you can answer it, or maybe you know someone who can. Or maybe you know a book that explains it. Any information to help me with this question would be appreciated. The question is this: My understanding of rebirth is that only a karmically-fueled psychological remnant is reborn in the next life. It’s not ‘We’ who are reborn, but our karmic tendencies that are reborn into a different body with brand new aggregates unrelated to the aggregates that we now possess. So, if it isn’t ‘We’ who is reborn, it is another entity that is merely a continuum of us, but not us, then how does Karma work in the next life? It doesn’t seem logical that one’s personal karma would affect a separate entity in the next life any more than it makes sense that someone else in this life would suffer karmically if we robbed a bank. Since one’s karma cannot be ‘transferred’ to another being, how does karma work in the next life? A person’s bad karma in this life should not logically affect a separate entity in another life. That’s not how karma works. We are all ‘heirs’ of our own karma the Buddha said. But if it’s not ‘We’ who is reborn, then how are ‘We’ heirs to some past entities Karma, and how is some future entity heir to our karma? Thanks in advance for your response.”

We apologize, in advance, that we cannot directly answer such an in-depth question with certainty.

Buddha Answers: “Let Go of Views”

The best answer, of course, is to quote the Buddha, although, in truth, his words should be contextual (and for that reason we append the entire referenced Sutta below):

Buddha: “Just as a person would cross a river on a raft and then leave it behind once he had reached the other shore, so too a person who sees the Dhamma should let go of views.”

Buddha taught countless students during his 80-year life. His teachings are captured in thousands of sutras (suttas).

Remember — We Don’t Always Remember

Before we answer with more Sutta and Discourse quotes below, of course, it’s worth discussing the impermanance of memories. If we self-identify with our happy or sad past memories, we are clinging. If we live, as Buddha taught, a virtuous life of positive activities (karma) we have a purpose. If we are born into a new life without memory of the “me” that was, and memories from previous lives, we should still celebrate.

In this life, most of us have memories in this life we suppress. We bury bad memories. We have forgotten childhood memories. We rarely remember our dreams — unless we engage in a conscious attempt to remember them. Many unpleasant — and often traumatic events — in this very life, we forget. This is, in part, a natural defense mechanism of “mind.”

The fact that we don’t remember clearly that we broke our leg when we were two, doesn’t mean we didn’t. We may, in fact, feel long term pain in our joints as we age. Not having a memory, doesn’t mean we don’t bear the consequence. A “criminal” who claims amnesia, can’t escape punishment for that reason.

Rebirth is a central concept in Buddhism.

If it is not “We” or “Me” who is reborn — why care?

In fact, as shown by the story of Buddha’s own Enlightenment, once we attain nirvana, all memories of past lives are revealed to us. These are expressed, for example, in the Jataka Tales. So, while we may not have a memory of past lives in each succeeding life — more or less to protect us from the additional burden of fear, painful memories and burdens — we do bear the consequences of our actions. Karma is a universal truth that cannot be extinguished. It can only be managed. By removed the causes of negative karmas, we can work, step by step, in life to life, towards our own ultimate Enlightenment.

So, why care? Because, just as we don’t remember childhood trauma — until, perhaps later — we likewise, in our journey through lives, will, like the Buddha, ultimately remember all of our past lives.

In fact, there are psychologists who engage in “past life regression” therapy to try to uncover past causes of trauma that may help us heal in this life. Imagine the size of the “chip” on our shoulders if we were born with full memories as a baby. We would never be able to progress and grow.

Rebirth as a belief causes some difficulty for students new to Buddhism and Agnostic Buddhists.

A Past Life Therapist’s View

Irina Nola, a past life therapist explains: “You do not remember past live consciously, however you do have those memories deep in your subconscious mind. There are plenty of things you do not remember in THIS life – your pre-natal existence, birth, early childhood, and plenty of day-by-day memories which just float to the bottom of your subconscious mind. You do not remember dreams usually, unless you train yourself in dream recall. You might not remember unpleasant events, as psychological defense mechanisms block them from conscious mind. And all of this affect your decisions and emotions without any conscious knowing.” [1]

In terms of the “reason” or logic for not remembering past lives: “If we remembered our past lives – it would be quite difficult for us to deal with current life…”

A baby is born happy — with no memory of past lives. Imagine the horrible crushing weight of being born, as a newborn, with full memory of past lives?

A baby is born happy — with no memory of past lives. Imagine the horrible crushing weight of being born, as a newborn, with full memory of past lives?

Buddha Discussed the Fear of Destruction of Self

In the Alagaddupama Sutta, the Buddha describes how some individuals feared his teaching because they believe that their self would be destroyed if they followed it. He describes this as an anxiety caused by the false belief in an unchanging, everlasting self. All things are subject to change and taking any impermanent phenomena to be a self causes suffering. Nonetheless, his critics called him a nihilist who teaches the annihilation and extermination of an existing being. The Buddha’s response was that he only teaches the cessation of suffering. When an individual has given up craving and the conceit of ‘I am’ their mind is liberated, they no longer come into any state of ‘being‘ and are no longer born again.

The Nature of Existence: Aggi-Vacchagotta Sutta

The Aggi-Vacchagotta Sutta records a conversation between the Buddha and an individual named Vaccha that further elaborates on existence. In the sutta, Vaccha asks the Buddha to confirm one of the following, with respect to the existence of the Buddha after death:[40]

- After death a Buddha reappears somewhere else

- After death a Buddha does not reappear

- After death a Buddha both does and does not reappear

- After death a Buddha neither does nor does not reappear.

The Buddha refused to answer any of these, stating that they were all matters of speculation. He explained that no one knows what happens after death and that it is best to focus on the here and now. In this way, one can work towards liberation rather than becoming preoccupied with unanswerable questions about the afterlife.

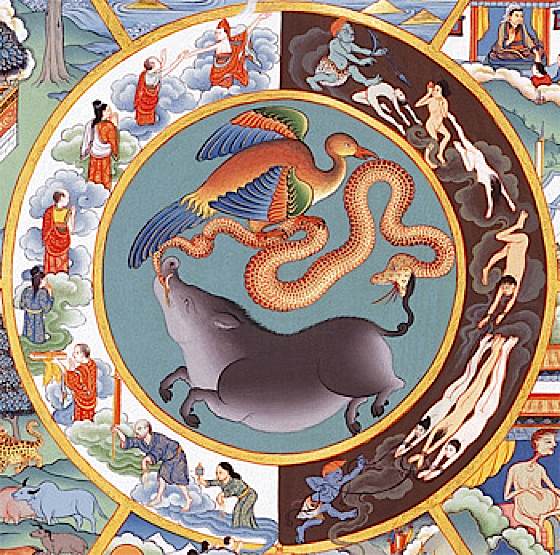

The concept of clinging, suffering and karma are bound up in the cycle of rebirth in Buddhism. In this image, the three poisons are represented by the pig, snake and bird, each biting each other. Around the circle are different lives, from birth to old age to the “bardo” which symbolizes the transition to the next life.

Karma, a handcuff?

In Buddha’s teachings, he focused on conduct in the hear-and-now and purification and other methods designed to help release us from the wheel of suffering — or Samsara. Until we are ultimately released, we are still “relatively” bound by Karma.

In fact, we could say, Karma is the handcuff that binds us to the wheel of suffering. (There were no handcuffs in Buddha’s time; feel free to think in terms of “binding” or “rope.”)

All well in good, you say, but what about a more practical answer that takes into account that most of us reading this are not likely ready to attain Enlightenment — at least not right now? (Time being relative, of course!)

Many of Buddha’s core teachings are represented in the iconic Tibetan Wheel of Life tangkha, including the three poisons (near the centre) and the 12 links of Dependent Co-Arising in the outside ring. Everything is represented as connected, interdependent and cyclic — like Samsara itself, the cycle of suffering, birth, death and rebirth.

Ultimate vs Relative Answers

To put context on this question, it’s important to realize that Buddhism recognizes that — until we attain Enlightenment — we are still bound to karma, which implies we are still bound to incorrect notions of “self.”

Extinguishing the self has nothing to do with Extinguishing existence. In the doctrine of Shunyata — a “boundless” full concept rather than an “empty” one — it is clear that all designations, all assertions about reality are only relatively true. So “self” and “other” are also only relatively true.

The simile of the flame and the light

This is a difficult concept to understand and it is often explained in terms of the relationship between a flame and its light. The flame is one entity but the light appears and disappears. In the same way, our Buddha Nature is one understanding, but the appearances of “other” are due to karmic conditioning. It is the “other” we think of as “self.” It is this “self” that craves, angers, hates, and is bound to karma and samsara.

From an ultimate perspective, there is no self or other, just the ceaseless flow of phenomena.

In the Alagaddupama Sutta he describes how

“All things are subject to change and taking any impermanent phenomena to be a self causes suffering.”

Practicing generosity creates positive karma. Here, a kind lay-Buddhist gives alms to three monks who, like the Buddha, eat only before noon and only from food given to them. Merit for good deeds is an intuitive concept in karma.

Karma and Rebirth in this Context

So how does karma work in the next life? In terms of rebirth, we could say that the “self” that is reborn is not the same self that was experiencing this life. It is another entity, but it’s still a continuum of us. This is why conduct in this life is so important — because it determines the kind of experience we will have in the next life.

Yet, this is the very fear — the extinguishing of “self” that led to Buddha’s discussion in Alagaddupama Sutta . People were afraid that if there is no self, then what happens to their good deeds and bad deeds? Who receives the rewards and punishment? (The very question our reader asks).

The Buddha’s answer was that it is another entity that is reborn, but not the same self. This other entity is still conditioned by our karma from this life. So good deeds result in a better rebirth and bad deeds result in a worse rebirth.

However, it’s important to realize that the karmic consequences of our actions are not just for this life, but for many lives to come. This is because the “self” that is reborn is conditioned by our karma from many past lives.

So, in answer to our reader’s question, we could say that the karmic consequences of our actions are not just for this life, but for many lives to come. Yet, this isn’t the actual logic from his question. K.D. asked:

“It doesn’t seem logical that one’s personal karma would affect a separate entity in the next life any more than it makes sense that someone else in this life would suffer karmically if we robbed a bank. Since one’s karma cannot be ‘transferred’ to another being, how does karma work in the next life?”

Conditional Rebirth

This is a difficult question to answer, but one way to think about it is that the “self” that is reborn is conditioned by our karma from this life. Since the cause of suffering is clinging to self, we tend to “forget” our past lives — it’s almost a self-defence. Imagine the horror of being born as a baby with memories of the worst horrors of dozens of previous lives. This “forgetfulness) is rooted in modern-day psychology (see below.)

The consequences carry forward, but the “baggage” of the self that suffered in the past life is mostly suppressed — just as we tend to suppress unhappy childhood memories in this life.

Or, to use a modern computer metaphor, the memories have been erased, but the hard drive (or flash drive, or cloud drive) still contains the information. It could be recovered. It is probably for the best, that we do not recover “past lives” memories, since that would create significant opportunities for additional clinging, attachments, and suffering. We’d be born with hates and prejudices.

In other words, we bear the responsibility for our past attachments, hates, poisons — but we start off with the advantage of a “fresh start” in the memory department. To use a different metaphor, even though we wake up in a new “prison” we have an opportunity to serve our “sentence” without the guilt, and to ultimately — potentially — earn our “release.” If on the other hand, we follow Buddha’s advice in “this lifetime” we have the potential to be reborn into a better life — a kinder prison.

Small acts of kindness create positive karma. The logic of karma is cause and effect, although its impact from one life to the next can be more a matter of faith or belief.

Wrong views and six views

In the Alagaddupama Sutta (full Sutta below), Buddha said,

“Bhikkhus, the ordinary man who has not seen the noble ones and Great Beings, not clever in their Teaching, and not trained in their Teaching Sees matter: that is me, I am that, that is my self. Sees feelings,; that is me, I am that, that is my self. Sees determinations: that is me, I am that, that is my self. Whatever seen, heard, tasted, smelt and bodily felt, cognized, attained, sought after, and reflected in the mind: that is me, I am that, that is my self The world, the self, I will be in the future, permanent, not changing, an eternal thing.; that is me, I am that, that is my self.”

This was only one of the six “views” Buddha described in the Sutta. What becomes clear, though, by the fact there are six views, is that from life to life, depending on our “obscurations” we will likely hold one of the six views. The entire Sutta, in fact, as explained by Thanissaro Bhikkhu in a commentary,

“This is a discourse about clinging to views (ditthi). Its central message is conveyed in two similes, among the most famous in the Canon: the simile of the water-snake and the simile of the raft. Taken together, these similes focus on the skill needed to grasp right view properly as a means of leading to the cessation of suffering, rather than an object of clinging, and then letting it go when it has done its job.”

In the first simile, the Buddha said that “just as a water-snake, thrown onto dry land, would struggle until it died,” so too does the person who clings to views. In the second, he compares views to a raft: “just as a person would cross a river on a raft and then leave it behind once he had reached the other shore, so too a person who sees the Dhamma should let go of views.”

In other words, clinging to any view — including the view that there is an eternal self — only leads to bondage and suffering. The good news is that we can “let go” of views, and in fact, this is the very aim of the Buddhist path.

Karma in the next life?

So, how does Karma work in the next life? Rebirth is a complex process that is not easily reducible to a single answer. As explained by Thanissaro Bhikkhu,

“The principle of karma is simple: intentional actions lead to consequences. However, the results of those actions are not always predictable, because they hinge not just on our own actions but also on the intentions and actions of other beings. The principle applies both to good and bad actions. Good actions lead to favorable consequences, bad actions to unfavorable ones. But the consequences can be mitigated by many factors, including our own efforts to offset them and the goodwill of other beings.”

In short, it is difficult to say exactly how Karma works in the next life, since there are so many factors at play. However, what we can say is that the principle of Karma is fair and just, and that ultimately, it leads to happiness and liberation.

Mocking a person, gossip, harsh talk are all “misconducts” that hurt other people and therefore also hurt yourself. The negative karma of these acts is a step towards “darkness.” In the teachings this means we carry this negative conduct into all our lives.

Our Readers Question and Arittha

K.D.’s question is similar to the one asked in the Sutta by Arittha, “that just because an idea can be logically inferred from the Dhamma does not mean that the idea is valid or useful. The Buddha himself makes the same point in AN 2.25:

“He who explains a discourse whose meaning needs to be inferred as one whose meaning has already been fully drawn out. And he who explains a discourse whose meaning has already been fully drawn out as one whose meaning needs to be inferred…”

Thanissaro Bhikkhu continues his commentary: “The second mistaken inference is that, given the thoroughness with which the Buddha teaches not-self, one should draw the inference that there is no self..”

One method taught in Vajrayana Buddhism is “self visualization.” The entire meditation helps us release false ego notions of “self” and helps us see ourselves as we really are — part of boundlessness. In this meditation method, we bring ourselves into a mindful state and a peaceful state, then we visualize our “present life” body into “clear light.” This doctrine of Shunyata has been translated as “emptiness” but is more “fullness”or “oneness” or “boundlessness.” In this state of “boundlessness”, we can visualize ourselves appearing in a Buddha Form. By acting as if we’re already “enlightened” we get a taste of realizations, and progress towards true realizations at a faster pace — hence the term Vajrayana, or Lightning Path (fast path).

With Self and “Me” Come Views

We try to reorganize our thinking away from “me” and “self” as a method. As with most things in Buddhism, Buddha taught “method.” The logic of Karma was not established by Buddha. Instead, he tried to help us deal with it. Buddha, as recorded in MN 2, said:

“I have a self… I have no self… It is precisely by means of self that I perceive self… It is precisely by means of self that I perceive not-self… It is precisely by means of not-self that I perceive self… or… This very self of mine — the knower that is sensitive here & there to the ripening of good and bad actions — is the self of mine that is constant, everlasting, eternal, not subject to change, and will endure as long as eternity. This is called a thicket of views, a wilderness of views, a contortion of views, a writhing of views, a fetter of views. Bound by a fetter of views, the uninstructed run-of-the-mill person is not freed from birth, aging, and death, from sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, and despair. He is not freed, I tell you, from suffering and stress.”

Shakyamuni saves Angulimala from himself. The mass murderer tries to take Buddha as his 1000th victim. When he fails, he falls to Buddha’s feet and asks to be taken as a monk. Although Buddha agrees, Angulimala must endure endless beatings at the hands of his victim’s families to help purify his negative karma. The time to purify negative karma is in this very lifetime, while we have the opportunity.

Sorry K.D. no simple, clear answers — and I’m afraid we didn’t really answer you precisely (simply because we probably can’t.) This very topic is at the heart of many Sutta discourses, starting with the Alagagadduupama Sutta and the Simile of the Snake:

Alagagadduupama Sutta and the Simile of the Snake

I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was staying in Savatthi, at Jeta’s Grove, Anathapindika’s park. Now on that occasion this pernicious viewpoint (ditthigata) had arisen in the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers: “As I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in, are not genuine obstructions.” A large number of monks heard, “They say that this pernicious viewpoint has arisen in the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers: ‘As I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in, are not genuine obstructions.’” So they went to the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers and on arrival said to him, “Is it true, friend Arittha, that this pernicious viewpoint has arisen in you — ‘As I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in, are not genuine obstructions’?”

“Yes, indeed, friends. I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, and those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in are not genuine obstructions.”

Then those monks, desiring to pry the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers away from that pernicious viewpoint, quizzed him back and forth and rebuked him, saying, “Don’t say that, friend Arittha. Don’t misrepresent the Blessed One, for it is not good to misrepresent the Blessed One. The Blessed One would not say anything like that. In many ways, friend, the Blessed One has described obstructive acts, and when indulged in they are genuine obstructions. The Blessed One has said that sensual pleasures are of little satisfaction, much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. The Blessed One has compared sensual pleasures to a chain of bones: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. The Blessed One has compared sensual pleasures to a lump of flesh… a grass torch… a pit of glowing embers… a dream… borrowed goods… the fruits of a tree… a butcher’s ax and chopping block… swords and spears… a snake’s head: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks.” [1] And yet even though he was quizzed back & forth and rebuked by those monks, the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers, through stubbornness and attachment to that very same pernicious viewpoint, continued to insist, “Yes, indeed, friends. I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, and those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in are not genuine obstructions.”

So when the monks were unable to pry the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers away from that pernicious viewpoint, they went to the Blessed One and on arrival, having bowed down to him, sat to one side. As they were sitting there, they [told him what had happened.]

So the Blessed One told a certain monk, “Come, monk. In my name, call the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers, saying, ‘The Teacher calls you, friend Arittha.’”

“As you say, lord,” the monk answered and, having gone to the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers, on arrival he said, “The Teacher calls you, friend Arittha.”

“As you say, my friend,” the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers replied. Then he went to the Blessed One and, on arrival, having bowed down to him, sat to one side. As he was sitting there, the Blessed One said to him, “Is it true, Arittha, that this pernicious viewpoint has arisen in you — ‘As I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in, are not genuine obstructions’?”

“Yes, indeed, lord. I understand the Dhamma taught by the Blessed One, and those acts the Blessed One says are obstructive, when indulged in are not genuine obstructions.”

“Worthless man, from whom have you understood that Dhamma taught by me in such a way? Worthless man, haven’t I in many ways described obstructive acts? And when indulged in they are genuine obstructions. I have said that sensual pleasures are of little satisfaction, much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. I have compared sensual pleasures to a chain of bones: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. I have compared sensual pleasures to a lump of flesh… a grass torch… a pit of glowing embers… a dream… borrowed goods… the fruits of a tree… a butcher’s ax and chopping block… swords and spears… a snake’s head: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. But you, worthless man, through your own wrong grasp [of the Dhamma], have both misrepresented us as well as injuring yourself and accumulating much demerit for yourself, for that will lead to your long-term harm & suffering.”[2]

Then the Blessed One said to the monks, “What do you think, monks? Is this monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers even warm [3] in this Doctrine & Discipline?”

“How could he be, lord? No, lord.”

When this was said, the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers sat silent, abashed, his shoulders drooping, his head down, brooding, at a loss for words.

Then the Blessed One, seeing that the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers was sitting silent, abashed, his shoulders drooping, his head down, brooding, at a loss for words, said to him, “Worthless man, you will be recognized for your own pernicious viewpoint. I will cross-examine the monks on this matter.”

Then the Blessed One addressed the monks, “Monks, do you, too, understand the Dhamma as taught by me in the same way that the monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers does when, through his own wrong grasp, both misrepresents us as well as injuring himself and accumulating much demerit for himself?”

“No, lord, for in many ways the Blessed One has described obstructive acts to us, and when indulged in they are genuine obstructions. The Blessed One has said that sensual pleasures are of little satisfaction, much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. The Blessed One has compared sensual pleasures to a chain of bones: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. The Blessed One has compared sensual pleasures to a lump of flesh… a grass torch… a pit of glowing embers… a dream… borrowed goods… the fruits of a tree… a butcher’s ax and chopping block… swords and spears… a snake’s head: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks.”

“It’s good, monks, that you understand the Dhamma taught by me in this way, for in many ways I have described obstructive acts to you, and when indulged in they are genuine obstructions. I have said that sensual pleasures are of little satisfaction, much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. I have compared sensual pleasures to a chain of bones: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. I have compared sensual pleasures to a lump of flesh… a grass torch… a pit of glowing embers… a dream… borrowed goods… the fruits of a tree… a butcher’s ax and chopping block… swords and spears… a snake’s head: of much stress, much despair, & greater drawbacks. But this monk Arittha Formerly-of-the-Vulture-Killers, through his own wrong grasp [of the Dhamma], has both misrepresented us as well as injuring himself and accumulating much demerit for himself, and that will lead to this worthless man’s long-term harm & suffering. For a person to indulge in sensual pleasures without sensual passion, without sensual perception, without sensual thinking: That isn’t possible. [4]

The Water-Snake Simile

“Monks, there is the case where some worthless men study the Dhamma: dialogues, narratives of mixed prose and verse, explanations, verses, spontaneous exclamations, quotations, birth stories, amazing events, question & answer sessions [the earliest classifications of the Buddha’s teachings]. Having studied the Dhamma, they don’t ascertain the meaning (or: the purpose) of those Dhammas [5] with their discernment. Not having ascertained the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment, they don’t come to an agreement through pondering. They study the Dhamma both for attacking others and for defending themselves in debate. They don’t reach the goal for which [people] study the Dhamma. Their wrong grasp of those Dhammas will lead to their long-term harm & suffering. Why is that? Because of the wrong-graspedness of the Dhammas.

“Suppose there were a man needing a water-snake, seeking a water-snake, wandering in search of a water-snake. He would see a large water-snake and grasp it by the coils or by the tail. The water-snake, turning around, would bite him on the hand, on the arm, or on one of his limbs, and from that cause he would suffer death or death-like suffering. Why is that? Because of the wrong-graspedness of the water-snake. In the same way, there is the case where some worthless men study the Dhamma… Having studied the Dhamma, they don’t ascertain the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment. Not having ascertained the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment, they don’t come to an agreement through pondering. They study the Dhamma both for attacking others and for defending themselves in debate. They don’t reach the goal for which [people] study the Dhamma. Their wrong grasp of those Dhammas will lead to their long-term harm & suffering. Why is that? Because of the wrong-graspedness of the Dhammas.

“But then there is the case where some clansmen study the Dhamma… Having studied the Dhamma, they ascertain the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment. Having ascertained the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment, they come to an agreement through pondering. They don’t study the Dhamma either for attacking others or for defending themselves in debate. They reach the goal for which people study the Dhamma. Their right grasp of those Dhammas will lead to their long-term welfare & happiness. Why is that? Because of the right-graspedness of the Dhammas.

“Suppose there were a man needing a water-snake, seeking a water-snake, wandering in search of a water-snake. He would see a large water-snake and pin it down firmly with a cleft stick. Having pinned it down firmly with a forked stick, he would grasp it firmly by the neck. Then no matter how much the water-snake might wrap its coils around his hand, his arm, or any of his limbs, he would not from that cause suffer death or death-like suffering. Why is that? Because of the right-graspedness of the water-snake. In the same way, there is the case where some clansmen study the Dhamma… Having studied the Dhamma, they ascertain the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment. Having ascertained the meaning of those Dhammas with their discernment, they come to an agreement through pondering. They don’t study the Dhamma either for attacking others or for defending themselves in debate. They reach the goal for which people study the Dhamma. Their right grasp of those Dhammas will lead to their long-term welfare & happiness. Why is that? Because of the right-graspedness of the Dhammas. [6]

“Therefore, monks, when you understand the meaning of any statement of mine, that is how you should remember it. But when you don’t understand the meaning of any statement of mine, then right there you should cross-question me or the experienced monks.

The Raft Simile

“Monks, I will teach you the Dhamma compared to a raft, for the purpose of crossing over, not for the purpose of holding onto. Listen & pay close attention. I will speak.”

“As you say, lord,” the monks responded to the Blessed One.

The Blessed One said: “Suppose a man were traveling along a path. He would see a great expanse of water, with the near shore dubious & risky, the further shore secure & free from risk, but with neither a ferryboat nor a bridge going from this shore to the other. The thought would occur to him, ‘Here is this great expanse of water, with the near shore dubious & risky, the further shore secure & free from risk, but with neither a ferryboat nor a bridge going from this shore to the other. What if I were to gather grass, twigs, branches, & leaves and, having bound them together to make a raft, were to cross over to safety on the other shore in dependence on the raft, making an effort with my hands & feet?’ Then the man, having gathered grass, twigs, branches, & leaves, having bound them together to make a raft, would cross over to safety on the other shore in dependence on the raft, making an effort with his hands & feet. [7] Having crossed over to the further shore, he might think, ‘How useful this raft has been to me! For it was in dependence on this raft that, making an effort with my hands & feet, I have crossed over to safety on the further shore. Why don’t I, having hoisted it on my head or carrying it on my back, go wherever I like?’ What do you think, monks: Would the man, in doing that, be doing what should be done with the raft?”

“No, lord.”

“And what should the man do in order to be doing what should be done with the raft? There is the case where the man, having crossed over, would think, ‘How useful this raft has been to me! For it was in dependence on this raft that, making an effort with my hands & feet, I have crossed over to safety on the further shore. Why don’t I, having dragged it on dry land or sinking it in the water, go wherever I like?’ In doing this, he would be doing what should be done with the raft. In the same way, monks, I have taught the Dhamma compared to a raft, for the purpose of crossing over, not for the purpose of holding onto. Understanding the Dhamma as taught compared to a raft, you should let go even of Dhammas, to say nothing of non-Dhammas.”

Six View-Positions

“Monks, there are these six view-positions (ditthitthana). Which six? There is the case where an uninstructed, run-of-the-mill person — who has no regard for noble ones, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma; who has no regard for men of integrity, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma — assumes about form: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“He assumes about feeling: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“He assumes about perception: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“He assumes about fabrications: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“He assumes about what seen, heard, sensed, cognized, attained, sought after, pondered by the intellect: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“He assumes about the view-position — ‘This cosmos is the self. [8] After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity’: ‘This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.’

“Then there is the case where a well-instructed disciple of the noble ones — who has regard for noble ones, is well-versed & disciplined in their Dhamma; who has regard for men of integrity, is well-versed & disciplined in their Dhamma assumes about form: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“He assumes about feeling: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“He assumes about perception: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“He assumes about fabrications: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“He assumes about what seen, heard, sensed, cognized, attained, sought after, pondered by the intellect: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“He assumes about the view-position — ‘This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity’: ‘This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.’

“Seeing thus, he is not agitated over what is not present.” [9]

When this was said, a certain monk said to the Blessed One, “Lord, might there be agitation over what is externally not present?”

“There might, monk,” the Blessed One said. “There is the case where someone thinks, ‘O, it was mine! O, what was mine is not! O, may it be mine! O, I don’t obtain it!’ He grieves & is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, & grows delirious. It’s thus that there is agitation over what is externally not present.”

“But, lord, might there be non-agitation over what is externally not present?”

“There might, monk,” the Blessed One said. “There is the case where someone doesn’t think, ‘O, it was mine! O, what was mine is not! O, may it be mine! O, I don’t obtain it!’ He doesn’t grieve, isn’t tormented, doesn’t weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. It’s thus that there is non-agitation over what is externally not present.”

Agitation & Non-Agitation

“But, lord, might there be agitation over what is internally not present?”

“There might, monk,” the Blessed One said. “There is the case where someone has this view: ‘This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity.’ He hears a Tathagata or a Tathagata’s disciple teaching the Dhamma for the elimination of all view-positions, determinations, biases, inclinations, & obsessions; for the stilling of all fabrications; for the relinquishing of all acquisitions; the ending of craving; dispassion; cessation; Unbinding. The thought occurs to him, ‘So it might be that I will be annihilated! So it might be that I will perish! So it might be that I will not exist!’ He grieves & is tormented, weeps, beats his breast, & grows delirious. It’s thus that there is agitation over what is internally not present.”

“But, lord, might there be non-agitation over what is internally not present?”

“There might, monk,” the Blessed One said. “There is the case where someone doesn’t have this view: ‘This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity.’ He hears a Tathagata or a Tathagata’s disciple teaching the Dhamma for the elimination of all view-positions, determinations, biases, inclinations, & obsessions; for the stilling of all fabrications; for the relinquishing of all acquisitions; the ending of craving; dispassion; cessation; Unbinding. The thought doesn’t occur to him, ‘So it might be that I will be annihilated! So it might be that I will perish! So it might be that I will not exist!’ He doesn’t grieve, isn’t tormented, doesn’t weep, beat his breast, or grow delirious. It’s thus that there is non-agitation over what is internally not present.”

Abandoning Possessions & Views

“Monks, you would do well to possess that possession, the possession of which would be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change, that would stay just like that for an eternity. But do you see that possession, the possession of which would be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change, that would stay just like that for an eternity?”

“No, lord.”

“Very good, monks. I, too, do not envision a possession, the possession of which would be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change, that would stay just like that for an eternity.

“Monks, you would do well to cling to that clinging to a doctrine of self, clinging to which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair. But do you see a clinging to a doctrine of self, clinging to which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair?”

“No, lord.”

“Very good, monks. I, too, do not envision a clinging to a doctrine of self, clinging to which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair.

“Monks, you would do well to depend on a view-dependency (ditthi-nissaya), depending on which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair. But do you see a view-dependency, depending on which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair?”

“No, lord.”

“Very good, monks. I, too, do not envision a view-dependency, depending on which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, & despair.

“Monks, where there is a self, would there be [the thought,] ‘belonging to my self’?”

“Yes, lord.”

“Or, monks, where there is what belongs to self, would there be [the thought,] ‘my self’?”

“Yes, lord.”

“Monks, where a self or what belongs to self are not pinned down as a truth or reality, then the view-position — ‘This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity’ — Isn’t it utterly & completely a fool’s teaching?”

“What else could it be, lord? It’s utterly & completely a fool’s teaching.”

“What do you think, monks — Is form constant or inconstant?” “Inconstant, lord.” “And is that which is inconstant easeful or stressful?” “Stressful, lord.” “And is it fitting to regard what is inconstant, stressful, subject to change as: ‘This is mine. This is my self. This is what I am’?”

“No, lord.”

“…Is feeling constant or inconstant?” “Inconstant, lord.”…

“…Is perception constant or inconstant?” “Inconstant, lord.”…

“…Are fabrications constant or inconstant?” “Inconstant, lord.”…

“What do you think, monks — Is consciousness constant or inconstant?” “Inconstant, lord.” “And is that which is inconstant easeful or stressful?” “Stressful, lord.” “And is it fitting to regard what is inconstant, stressful, subject to change as: ‘This is mine. This is my self. This is what I am’?”

“No, lord.”

“Thus, monks, any form whatsoever that is past, future, or present; internal or external; blatant or subtle; common or sublime; far or near: every form is to be seen as it actually is with right discernment as: ‘This is not mine. This is not my self. This is not what I am.’

“Any feeling whatsoever…

“Any perception whatsoever…

“Any fabrications whatsoever…

“Any consciousness whatsoever that is past, future, or present; internal or external; blatant or subtle; common or sublime; far or near: every consciousness is to be seen as it actually is with right discernment as: ‘This is not mine. This is not my self. This is not what I am.’

“Seeing thus, the instructed disciple of the noble ones grows disenchanted with form, disenchanted with feeling, disenchanted with perception, disenchanted with fabrications, disenchanted with consciousness. Disenchanted, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion, he is fully released. With full release, there is the knowledge, ‘Fully released.’ He discerns that ‘Birth is ended, the holy life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world.’

“This, monks, is called a monk whose cross-bar is thrown off, [10] whose moat is filled in, whose pillar is pulled out, whose bolt is withdrawn, a noble one with banner lowered, burden placed down, unfettered.

“And how is a monk one whose cross-bar is thrown off? There is the case where a monk’s ignorance is abandoned, its root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. This is how a monk is one whose cross-bar is thrown off.

“And how is a monk one whose moat is filled in? There is the case where a monk’s wandering-on to birth, leading on to further-becoming, is abandoned, its root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. This is how a monk is one whose moat is filled in.

“And how is a monk one whose pillar is pulled out? There is the case where a monk’s craving is abandoned, its root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. This is how a monk is one whose pillar is pulled out.

“And how is a monk one whose bolt is withdrawn? There is the case where a monk’s five lower fetters are abandoned, their root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. This is how a monk is one whose bolt is withdrawn.

“And how is a monk a noble one with banner lowered, burden placed down, unfettered? There is the case where a monk’s conceit ‘I am’ is abandoned, its root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. This is how a monk is a noble one with banner lowered, burden placed down, unfettered.

“And when the devas, together with Indra, the Brahmas, & Pajapati, search for the monk whose mind is thus released, they cannot find that ‘The consciousness of the one truly gone (tathagata) [11] is dependent on this.’ Why is that? The one truly gone is untraceable even in the here & now. [12]

“Speaking in this way, teaching in this way, I have been erroneously, vainly, falsely, unfactually misrepresented by some brahmans and contemplatives [who say], ‘Gotama the contemplative is one who misleads. He declares the annihilation, destruction, extermination of the existing being.’ But as I am not that, as I do not say that, so I have been erroneously, vainly, falsely, unfactually misrepresented by those venerable brahmans and contemplatives [who say], ‘Gotama the contemplative is one who misleads. He declares the annihilation, destruction, extermination of the existing being.’ [13]

“Both formerly and now, monks, I declare only stress and the cessation of stress. [14] And if others insult, abuse, taunt, bother, & harass the Tathagata for that, he feels no hatred, no resentment, no dissatisfaction of heart because of that. And if others honor, respect, revere, & venerate the Tathagata for that, he feels no joy, no happiness, no elation of heart because of that. And if others honor, respect, revere, & venerate the Tathagata for that, he thinks, ‘They do me such service at this that has already been comprehended.’ [15]

“Therefore, monks, if others insult, abuse, taunt, bother, & harass you as well, you should feel no hatred, no resentment, no dissatisfaction of heart because of that. And if others honor, respect, revere, & venerate you as well, you should feel no joy, no gladness, no elation of heart because of that. And if others honor, respect, revere, & venerate you, you should think, ‘They do us [16] such service at this that has already been comprehended.’

“Therefore, monks, whatever isn’t yours: Let go of it. Your letting go of it will be for your long-term welfare & happiness. And what isn’t yours? Form (body) isn’t yours: Let go of it. Your letting go of it will be for your long-term welfare & happiness. Feeling isn’t yours… Perception… Thought fabrications… Consciousness isn’t yours: Let go of it. Your letting go of it will be for your long-term welfare & happiness.

“What do you think, monks: If a person were to gather or burn or do as he likes with the grass, twigs, branches & leaves here in Jeta’s Grove, would the thought occur to you, ‘It’s us that this person is gathering, burning, or doing with as he likes’?”

“No, lord. Why is that? Because those things are not our self, nor do they belong to our self.”

“Even so, monks, whatever isn’t yours: Let go of it. Your letting go of it will be for your long-term welfare & happiness. And what isn’t yours? Form isn’t yours… Feeling isn’t yours… Perception… Thought fabrications… Consciousness isn’t yours: Let go of it. Your letting go of it will be for your long-term welfare & happiness.

The Well-Proclaimed Dhamma

“The Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags. In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — there is for those monks who are arahants — whose mental effluents are ended, who have reached fulfillment, done the task, laid down the burden, attained the true goal, totally destroyed the fetter of becoming, and who are released through right gnosis — no (future) cycle for manifestation. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags. [17]

“In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — those monks who have abandoned the five lower fetters are all due to be reborn [in the Pure Abodes], there to be totally unbound, never again to return from that world. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags.

“In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — those monks who have abandoned the three fetters, with the attenuation of passion, aversion, & delusion, are all once-returners who, on returning only one more time to this world, will make an ending to stress. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags.

“In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — those monks who have abandoned the three fetters, are all stream-winners, steadfast, never again destined for states of woe, headed for self-awakening. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags.

“In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — those monks who are Dhamma-followers and conviction-followers [18] are all headed for self-awakening. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags.

“In the Dhamma thus well-proclaimed by me — clear, open, evident, stripped of rags — those monks who have a [sufficient] measure of conviction in me, a [sufficient] measure of love for me, are all headed for heaven. This is how the Dhamma well-proclaimed by me is clear, open, evident, stripped of rags.”

That is what the Blessed One said. Gratified, the monks delighted in the Blessed One’s words. [2]

NOTES

[1] Irina Nola, Past Life Therapist>>

[2] Citation “Alagaddupama Sutta: The Water-Snake Simile” (MN 22), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 17 December 2013, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.022.than.html .