[ad_1]

What do big moons, lazy nihilists and rabbit holes have to do with Shunyata? Yesterday I read a feature on Space.com which became the inspiration of this feature: “The ‘Big Moon’ Illusion May All Be in Your Head,” by Joe Rao. This led to rabbit holes and lazy nihilism. Bear with me, I come back to the big moon at the end, and I want to start with snakes.

Nagarjuna: “Wrong End of the Snake”

Famously, the great Nagarjuna is credited with saying: “Emptiness wrongly grasped is like picking up a poisonous snake by the wrong end.”

However perilous, serious Buddhists students have to try to pick up that snake. No one wants to be bitten. Recently, one of my good friends went back to her birth religion, after years as a Buddhist, because she couldn’t get past thinking she was practicing nihilism. She had picked up “the wrong end” of the snake. For most of the rest of us — who aspire to Buddhist realizations — it can be the most difficult of topics.

The great teacher Narajuna taught extensively on emptiness.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches that Emptiness is “the knowledge of ultimate reality of all objects, material and phenomenon.” [3]

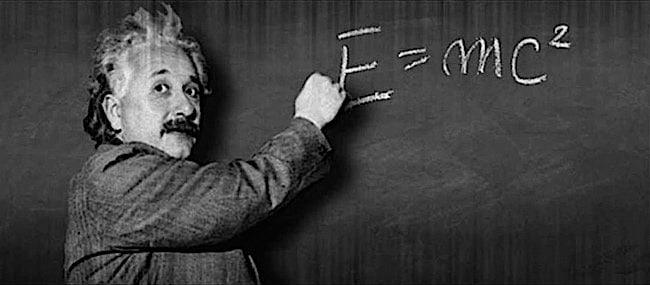

Einstein and “bullshit”: Substantialism versus Nihilism

The venerable teacher Gelek Rinpoche points to Einstein’s theory of relativity for a concise explanation of emptiness: “The theory of relativity gives you Buddha’s idea of emptiness. The essence of emptiness is the interdependent nature or dependent arising of things. The essence of Emptiness is not empty.” [7]

Einstein’s theory of relativity.

In separate teaching on Yamantaka — in his eloquent, direct teaching style — Gelek Rinpoche warned against nihilism: “So if some people say ‘Everything is only the result of mind. In the end, it is all zero, so it doesn’t matter, it’s all the same, it’s all bullshit’ … that is the emptiness approach from the empty point of view and that gets you on the wrong track.” [9]

The great Tibetan Yogini Machig explained emptiness as “the source and inseparable essence of all phenomena, it represents the totality of all that is and all that will come to be. For without emptiness, there would be no space for existence.”[8] This is the opposite of nihilism, and could be better described as “inclusivism” of “substantialism.” [11]

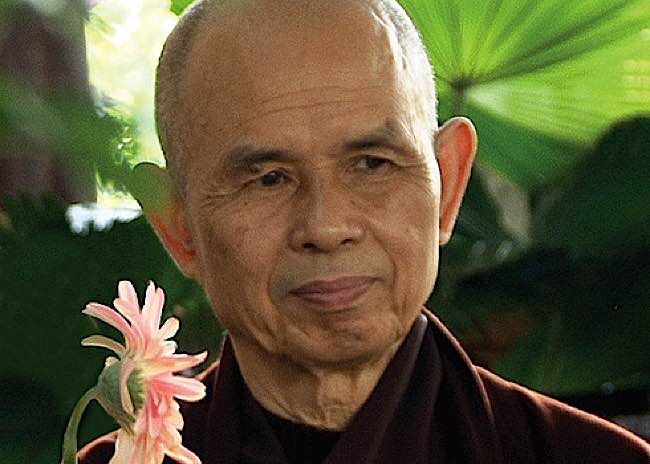

Thich Nhat Hanh: “Inter-Be”

The great Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh describes Emptiness as: “empty of separate self. That means none of the five [aggregates] can exist by itself alone. Each of the five [aggregates] has to be made up of the other four. It has to coexist; it has to inter-be with all others.” The term “Inter-Be” has become something of the modern-day equivalent to the Sanskrit term “Shunyata” with some Zen teachers. [12]

Thich Nhat Hanh, the great zen teacher.

Lama Tsongkhapa, in his Three Principles, writes: “Interdependent appearance — infallible Emptiness… As long as these two seem separate, Buddha’s insight is not understood.”

The problem with the extreme of substantialism arises when “things appear to exist from their own side so solidly that even when we recognize that they are empty in nature … they still appear to exist from their own side,” writes Rob Preece, in Preparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice. [10]

The problem with nihilism — substantialism’s opposite — is Nagarjuna’s venomous snake. Buddha taught “the middle way” which implies avoiding extreme views, such as substantialism and nihilism. Both concepts run contrary to the notion of emptiness.

IABS: “Transcend a lazy nihilism”

It is easy for people to make incorrect assumptions from the terms “Emptiness” and “Voidness” — incomplete, even possibly misleading translations of the Sanskrit word Shunyata. The International Association of Buddhist Studies (IABS), in their Journal, warns practitioners to “transcend a lazy nihilism” — one of the perceptions that arise from the terms Emptiness and Voidness. [2]

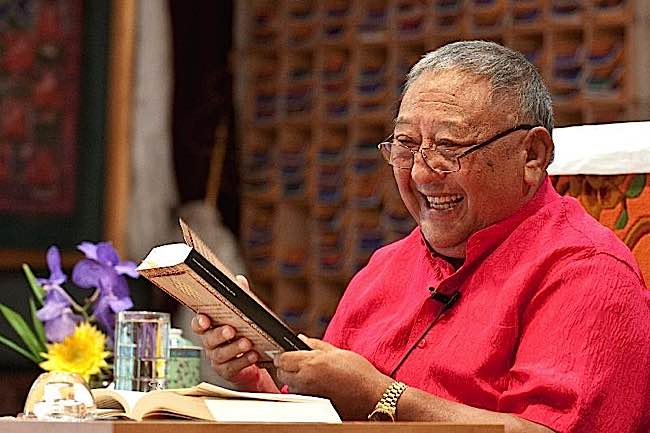

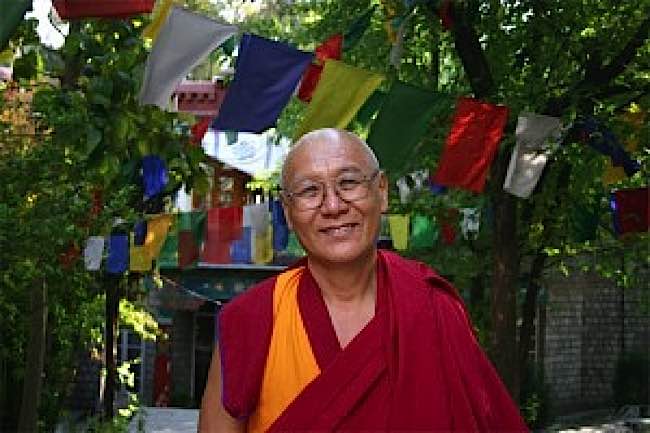

Zasep Tulku Rinpoche frequently cautions against nihilism in his formal teachings. Rinpoche meditates by the river in Mongolia.

Quite the contrary, as Terry Clifford explains in Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Buddhism, if emptiness was nihilistic, compassion would be pointless. “The absolute compassion of Mahayana arises spontaneously with the realization of emptiness. Since we all share the nature of emptiness, how can we bear the suffering of others…” [6]

Friend: “Aren’t You a Nihilist?”

The entire concept of Emptiness and Shunyata is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of Buddhism. My non-Buddhist friends often ask me, “Aren’t you a nihilist?” or “Why would you want to destroy ego? Isn’t that what makes us sentient beings?”

Sure, I could jump in and say, “You can’t destroy ego, because ego really doesn’t inherently exist,” but I don’t feel qualified to enter into a back-and-forth debate on dependent arising, labeling, and ego. I have answered, in the past, with direct quotes from the Buddha. Other times, I’ve used quotes from neurologists and psychologists, who tend to concur, for the most part, with the Buddha.

The greatest of teachers, Shakyamuni.

So, to help me answer (for myself) this recurring question from my friends of the non-Buddhist persuasion, I decided to research what the teachers of different traditions have to say about Emptiness. To spice it up, I’ve also searched out what physicists, psychiatrists and neurologists have to say about ego and self. I’ve brought some of these quotes together in this little feature with some helpful links to more details in the notes.

Milarepa: “Appearances are … superficial”

The great yogi Milarepa, in one of his One Hundred Thousand Songs sang: “Mind is insubstantial, void awareness, body a bubble of flesh and blood. If the two are indivisibly one, why would a corpse be left behind at the time of death when the consciousness leaves? And if they are totally separate why would the mind experience pain when harm happens to the body? Thus, illusory appearances are the result of belief in the reality of the superficial.” [1]

The great yogi Milarepa expounded on emptiness with concise clarity in his 100,000 songs.

In Milarepa’s time (born 1052 in Tibet), songs were used to enchant and teach, even on topics as difficult and profound as Emptiness. Today, we’d be as likely to cite or quote popular movies.

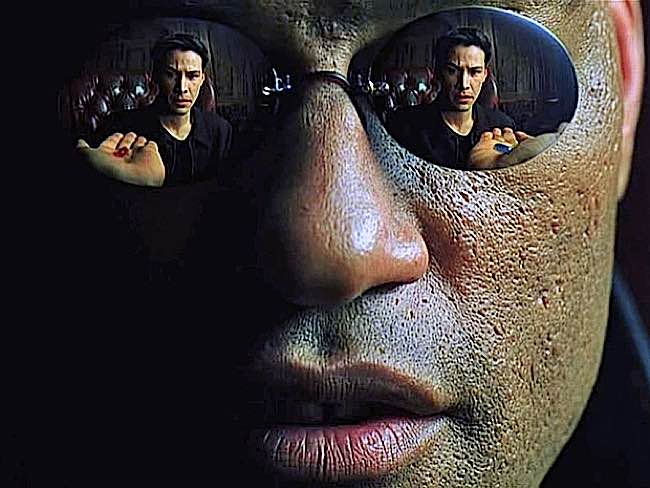

The Matrix: “How Deep the Rabbit Hole Goes”

For example, in the popular movie The Matrix, the character Morpheus (played by Laurence Fishburne) explains to Neo (played by Keanu Reaves) that the world is not as it seems. What Neo sees, he explains, is not the true nature of reality. (Note: he does not say the world does “not” exist.) He offers Neo, the hero of the story, a choice between a red pill or a blue pill:

“This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill—the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill—you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes. Remember: all I’m offering is the truth. Nothing more.”

“This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill—the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill—you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

The “waking up” language Morpheus used, is often used in Buddhism. We try to “wake up” to the true nature of reality in order to end suffering. In Buddhism — so it seems — at some point, we also have to choose the red pill or the blue pill. The sleeping metaphor is also often used by Buddhist teachers. Like Neo, many of us are tempted just to go back to sleep and “believe whatever” we want to believe.

Sure, it’s more complicated than a choice of two pills, but The Matrix movie offers, perhaps, one of the easiest ways to introduce the notion of Emptiness in Buddhism to the modern non-Buddhist — in much the same way as Milarepa used enchanting songs. So, borrowing from Morpheus, I set out to research what the great Buddhist teachers have to say about Emptiness, that most difficult of subjects — in pursuit of “the truth, nothing more” and “how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

Buddha: “Empty of Self”

In the Pali canon, Sunna Sutta, Ananada asks Buddha about emptiness:

“It is said that the world is empty, lord. In what respect is it said that the world is empty?” The Buddha replied, “Insofar as it is empty of a self or of anything pertaining to a self: Thus it is said, Ānanda, that the world is empty.””

This deceptively simple answer seems to satisfy my curious non-Buddhist friends when they ask about emptiness, but for the practicing Buddhist, it’s often just the beginning of understanding.

Shakyamuni Buddha, the current Buddha of our time.

Albert Einstein: “Reality is merely an illusion”

For those of more “scientific” orientation, Albert Einstein — who was not a Buddhist, despite being credited with saying: ” If there is any religion that would cope with modern scientific needs it would be Buddhism” — had this to say on the nature of reality:

“A human being is part of a whole, called by us the ‘universe’, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separate from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affectation for a few people near us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.” [6]

Gelek Rinpoche of Jewel Heart.

The venerable teacher Gelek Rinpoche, in his 7-day teachings on Vajrayogini, linked Einstien’s theory of relativity to Buddha’s teachings on Emptiness: “I begin to appreciate Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, based on points of reference. If you don’t have points of reference, you are gone. If there is no point of reference, there is no existence. Everything exists relatively, collectively, because of points of reference.” [7]

Quoting the Teachers: Just What is Emptiness?

If Emptiness is not nihilism, then what exactly is it? It can be challenging to try to understand such a vast (and yet not vast) topic such as Emptiness, especially from teacher snippets. Such extracts necessarily sound enigmatic and almost riddle-like. Teachers often deliberately challenge our mind with difficult propositions. Ultimately, it is for us to develop our own realizations. Here are some famous quotes on “Emptiness” from the great teachers of Buddhism:

“The four categories of existence, non-existence, both existence and non-existence, and neither existence nor non-existence, are spider webs among spider webs which can never take hold of the enormous bird of reality” — The Buddha (563 – 483 BC)

“After 48 years, I have said nothing.” — The Buddha

“Whatever depends on conditions is explained to be empty…” — Sutra Requested by Madropa, translated by Ari Goldfield

“We live in illusion and the appearance of things. There is a reality. We are that reality. When we understand this, we see that we are nothing. And being nothing, we are everything. That is all.” — Kalu Rinpoche [4]

“Once you know the nature of anger and joy is empty and you let them go, you free yourself from karma.” — Bodhidharma (c 440-528 AD) [5]

Bodhidharma, the great chan sage.

“The past is only an unreliable memory held in the present. The future is only a projection of our present conceptions. The present itself vanishes as soon as we try to grasp it. So why bother with attempting to establish an illusion of solid ground?” — Dilgo Kyentse

“What is Reality? An icicle forming in fire.” — Dogen Zenji (c 1200-1253 AD)

“Men are afraid to forget their minds, fearing to fall through the Void with nothing to stay their fall. They do not know that the Void is not really void, but the realm of the real Dharma.” — Huang-po (Tang Dynasty Zen Teacher)

Answering the Nihilist Challenge: Is Emptiness Nothingness or Voidness?

Even if the words of great teachers challenge us to our own understandings of Emptiness, there is always the risk of “lazy nihilism.” If we can’t understand such a profound concept, we often “lazily” associate Emptiness with Nihilism. [2]

The problem begins with the English translation of the original Sanskrit term Shunyata. This profound and complex concept is often translated into English as “voidness.” Voidness sounds a lot like “nothingness” and, in my many years of attending teachings, I’ve often heard teachers interchange the word Emptiness, Voidness and Nothingness, so this can be confusing from the get-go. In the same discussion, some teachers will warn against nihilism, but never-the-less use the word “nothingness.”

“There is really no adequate word in English for Shunyata, as both ‘voidness’ and ’emptiness’ have negative connotations, whereas, shunyata is a positive sort of emptiness transcending the duality of positive-negative,” writes Terry Clifford in Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry. [6] He adds: “The doctrine of void was propounded in the Madhyamika dialectic philosophy of Nagarjuna, the second-century Buddhist philosopher-saint. Nagarjuna said of shunyata, ‘It cannot be called void or not void, or both or neither, but in order to indicate it, it is called the Void.”

In Sanskrit, the word Shunyata has a very layered meaning, not easily translated into other languages. Translations of the Sanskrit noun Shunyata might be part of the issue. The Sanskrit noun Shunyata literally translates as “zero” or “nothing” — but like most Sanskrit words, a single-word translation is misleading. The Sanskrit adjective is actually Sunya, which means “empty” — according to translators who insist on single-word equivalents. In Buddhist concept, Shunyata is decidedly not nihilistic in tone — sometimes, it is translated as openess, oneness and spaciousness. No single-word translation is really helpful in describing the true essence of Shunyata.

How Different Traditions Describe Emptiness

Are there differences in how Shunyata is interpreted in the major schools of Buddhist thought? Most teachers will say Shunyata is Shunyata, and schools or philosophies just offer different ways of illustrating the concept. Here I’ll be overly simplistic (almost to the point of disservice).

The elder schools, Theravadan Buddhism, often translate sunnata or shunyata is as “non self” or “not self” in the context of the five aggregates of experience.

In Mahayana Buddhism, notably Prajna-Paramita Sutra, which means “Perfection of Wisdom”, the notion of Shunyata is equated to Wisdom. Mahayana teachers often stress that Enlightenment is only possible with realizations in Wisdom of Emptiness and Compassion—both are essential. In this Mahayana view, emptiness is beautifully expressed in the famous Heart sutra in these profound — if enigmatic — words:

Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.

Emptiness is not separate from form,

Form is not separate from emptiness.

Whatever is form is emptiness,

Whatever is emptiness is form.

We Are An Imputed Label

Mahayana teachers often focus more on the notion of “imputed labels” as an introduction to the very difficult subject of Emptiness. Imputing is a frequently repeated word in the teachings on Emptiness.

In teachings on Mahamudra in Ontario last spring, Venerable Zasep Tulku Rinpoche gave this example of labeling: “A good example is your car. If you take that car apart, and everything is just parts, there is no car. Just car parts. You put it back together, and then label it Hyundai, you have a Hyundai. But if you switch the labels [to Honda] is it now a Honda? It’s all labels. There is no independent existence. That’s only one way to look at emptiness.”

“A good example is your car. If you take that car apart, and everything is just parts, there is no car. Just car parts. You put it back together, and then label it Hyundai, you have a Hyundai.”

During a “scanning meditation” guided practice in the same teaching session at Gaden Choling, Zasep Rinpoche asked students to find their body: “what is my body? … do a scanning meditation and try to find your body. “When you scan your skin, you ask, is that my body? No, it’s skin, not body. Then you look at your bones, and likewise every part of your body… To be body, it has to be the ‘whole’ body, all the parts. If you really look, you can’t find one thing that is your body. What we call body is just a ‘label’. A name. Imputing a label.”

Labeling implies that we are more than our label, rather than less. It conveys a sense of expansiveness, oneness and fullness.

Geshe Tashi Tsering.

Four Different Views on Emptiness: Geshe Tashi Tsering

“Each of the four Buddhist philosophical schools presents emptiness differently,” writes Geshe Tsering in his powerful book, Tantra: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought. [4] Presenting differently, however, does not mean they disagree on the essence of Emptiness.

“There is the emptiness or selflessness asserted by the schools below Svatantrika -Madhyamaka, where the Hinayana schools — Vaibhashika and Sautrantika — assert emptiness is being empty of substantial existence, and the Chittamatra school explains emptiness as the absence of duality of appearance of subject and object. Svatantrika-Madhyamaka school explains it as being empty of existing from its own side without depending on the mind. Finally, there is the emptiness asserted in Prasangika-Madhyamaka, which is being empty of existing inherently.”

The earth also looks deceptively large rising above the horizon of the moon.

Big Moons: Where This Story Began

I was inspired to write this story from a feature on Space.com. It was a light-hearted story titled, “The ‘Big Moon’ Illusion May All Be in Your Head.” For decades, scientists and thinkers have pondered over the phenomenon of the giant moon, when viewed at the horizon. Aristotle theorized it was the magnifying effect of the image of the moon enlarged through the atmosphere (pretty smart, that Aristotle guy.) I actually thought that was the case.

“Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1865), an astronomer who was considered to be a master mathematician, proposed that the answer lay in the difference between the image perceived when the rising moon was viewed over a horizon, in which case nearby objects provided a sense of scale for the eye, and the image perceived when the eyes were raised to view the same object overhead.” The author of the piece, Joe Rao, went on to describe a “simple experiment…. Get hold of a cardboard tube… Now close one eye and with the other look at the seemingly enlarged moon near the horizon through the tube and immediately the moon will appear to contract to its normal proportions.”

So, how did this inspire my little feature on Emptiness and dependent arising? The first thing I thought of when I read Joe Rao’s story was, “dependent arising…” and how we perceive things through their relationship to each other. I know, it’s a stretch, but that was my inspiration.

NOTES

[1] Drinking the Mountain Stream: Songs of Tibet’s Beloved Saint Milarepa, translated by Lama Kunga Rinpoche and Brian Cutillo.

[2] “The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Volumes 11-12, page 108. IABS website: https://iabsinfo.net

[3] Buddhism Teacher: Emptiness https://buddhismteacher.com/emptiness.php

- [4] Tantra: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought, Volume 6 by Geshe Tashi Tsering

- Paperback: 240 pages; Publisher: Wisdom Publications (July 3 2012), ISBN-10: 1614290113; ISBN-13: 978-1614290117

- [5] Joseph Goldstein Interview https://www.dharma.org/ims/joseph_goldstein_interview1.html

- [5] “The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma: A Bilingual Edition.”

- [6] The Responsive Universe, John C. Bader, Wisdom Moon Publishing, ISBN-10: 1938459288, ISBN-13: 978-1938459283

- [7] “Vajrayogini”, PDF transcript, 490 pages, Jewel Heart (requires initiation from a qualified teacher to download). https://www.jewelheart.org/digital-dharma/vajrayogini/

- [8] Machik’s Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chod (Expanded Edition), Snow Lion, ASIN: B00DMC5HAQ

- [9] “Solitary Yamantaka Teachings”, PDF, 460 pages, Jewel Heart (requires initiation from a qualified teacher to download).

- [10] Preparing for Tantra: Creating the Psychological Ground for Practice, Rob Preece, Snow Lion, ASIN: B00FWX9AX8

- [11] Source of term substantialism: ” Some philosophers of physics take the argument to raise a problem for manifold substantialism, a doctrine that the manifold of events in spacetime is a “substance” which exists independently of the matter within it.”

- [12] The Heart of Understanding: Comentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra, Thich Nhat Hanh, Parallax Press, ASIN: B005EFWU0E

[ad_2]

Source link