[ad_1]

Former free-roaming nomads now mostly resettled in rows of sun-baked block houses in Tibet are facing a struggle for their identity, their spiritual and cultural practices – and even their stomachs.

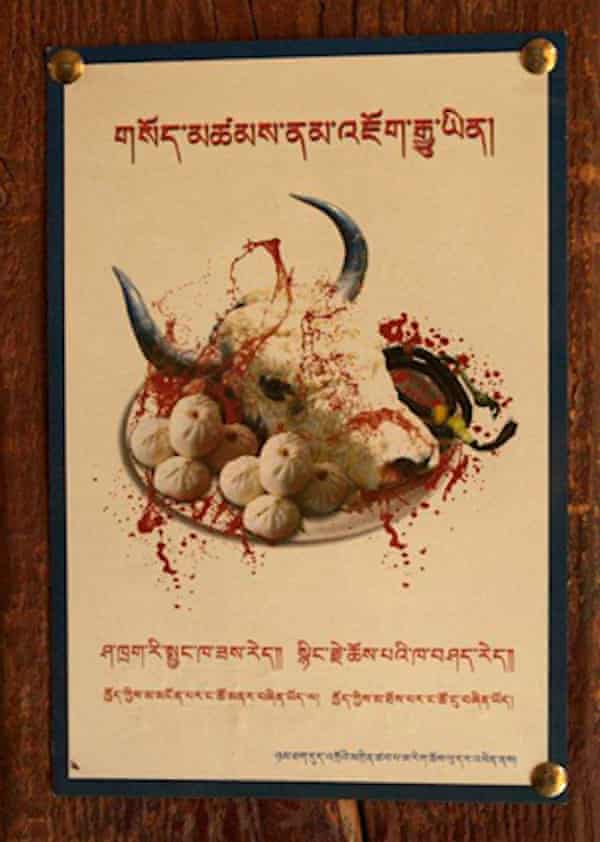

These yak-tending herders have always eaten meat. In addition to the milk, butter and cheese they derived from yaks, meat was a necessity in their harsh lives.

But a movement spurred by Tibetan Buddhist monks in the region over the past two decades has increasingly urged now sedentary nomads to practise vegetarianism, to pay a “life ransom” for the release of animals destined for the slaughterhouse, and to abandon the slaughter of their own animals because they have settled down.

That “anti-slaughter movement” has put them at odds with local authorities intent on driving development and the industrial production of yak meat for a Chinese public that is consuming more meat than ever before. The production drive has included the expansion of large numbers of commercial slaughterhouses to process the meat from the approximately 14 million yaks on the Tibetan plateau.

Chinese authorities appear to be winning this battle, at least in the physical realm.

“My impression is that the [anti-slaughter] movement is declining as a result of increased surveillance and repression that criminalises any movement asserting Tibetan identity,” says Katia Buffetrille, a French anthropologist and Tibetologist who has been travelling to Tibetan areas for more than three decades.

The sentencing last June of 10 Tibetans, including two monks, to jail terms of between eight to 13 years and fines of up to £7,000 each for trying to block the construction of a commercial slaughterhouse in Sangchu, Gansu province, has largely silenced discussion coming out of Tibetan areas about anti-slaughter beliefs.

‘Bad karma’ on the Tibetan plateau

The anti-slaughter movement first emerged around 2000 from the Larung Gar Buddhist Academy, famous from photos of its red-roofed shacks dotting a treeless alpine valley in the Garzê region of Sichuan. The spiritual oasis was home to an estimated 40,000 unofficial residents – monks and spirituality seekers – before the extensive destruction of the area and expulsion of a large number of monks since 2016.

An influential and now deceased monk at the Academy, Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok, taught against slaughterhouse practices after witnessing them first-hand. He said the sight inside slaughterhouses was, “similar to what we imagine as the town of death, full of terrifying noises including the sound of machines used to process meat, the sound from sliced throats, the sound of running blood, and moos of livestock in a deadly panic”.

He believed that huge commercial slaughterhouses would bring bad karma to the Tibetan plateau, and were alien to the practices nomads had followed for hundreds of years.

However, most Tibetans – and even many monks – did not practise vegetarianism, and it was only the wealthier herders who could afford to release animals for spiritual purposes.

“[Nomadic] Tibetans were never vegetarian. Now, many monasteries don’t give any more meat, but some allow to eat meat outside,” says Buffetrille, adding that nomads are caught between two alternatives.

“On the one hand, the Chinese state’s path of assimilation, which is depriving them of their specific culture, language and way of life. On the other hand, the clergy’s strategy, which requests nomads to follow the Tibetan religious way of life they advocate for, but that does not conform to their daily habits as lay and nomad Buddhists,” she says.

Traditionally, vegetarianism was widely practised in monasteries, but not among nomads, says Geoffrey Barstow, an expert on Tibetan Buddhism at Oregon State University, who said some nomads see the “no slaughter” movement as a threat to the practicalities of making enough money to survive.

“You can imagine how hard it would be as a nomad to be a vegetarian,” he says. “As for a full-out nomad being a vegetarian, I don’t have any records of anyone doing that.”

The issue, Barstow says, breaks down to people who see Buddhism as the fundamental “heart and soul” of Tibetan identity and those who see nomadism as the core of that identity.

Beijing cracks down on campaigners

In the end, neither the spiritual dimension nor the identity crisis among the nomads that China has ordered to stay put appear to be a consideration for Beijing. For local governments, under orders to increase GDP, anything that gets in the way challenges state power and authority.

Since 2018, when China’s leadership under Xi Jinping launched a three-year nationwide campaign against “black and evil” forces, local governments in Tibetan regions have increasingly cracked down on anyone organising in those areas outside government sanctioned activities.

Citizen groups trying to protect wildlife or the environment, those calling for increased food safety, religious and cultural activities, and those advocating against land-grabs, the construction of slaughterhouses, or for the freeing of animals as a spiritual practice have all been targeted as “underworld gangs” according to organisations including Human Rights Watch.

“One of the reasons they cited them as gangs was because they had been organising community members against a slaughterhouse in their home town,” Tenzin Norgay, a research analyst at the International Campaign for Tibet, told the Guardian.

“In some cases they have conflated the anti-slaughter movement with the issue of separatism, so when they pass these kinds of laws it definitely has some impact on the participants in this movement,” he says.

Since the nonviolent protests against the slaughterhouse took place several years ago, the court action is largely seen as a message to warn others against similar, future actions, he says.

In the months since that verdict Norgay has not heard from people in the region about similar anti-slaughter actions. He says it is “too risky”, since even communicating with people outside Tibet could be considered a crime.

Sign up for the Animals farmed monthly update to get a roundup of the best farming and food stories across the world and keep up with our investigations. You can send us your stories and thoughts at animalsfarmed@theguardian.com

[ad_2]

Source link